- How Parallel Circuit Execution Can Be Useful for NISQ Computing, DATE-2022

- A Case for Multi-Programming Quantum Computers, MICRO-2019

- QuCloud: A New Qubit Mapping Mechanism for Multi-programming Quantum Computing in Cloud Environment, HPCA-2021

- Stealthy SWAPs: Adversarial SWAP Injection in Multi-Tenant Quantum Computing, arXiv, 2023

- Enabling Multi-programming Mechanism for Quantum Computing in the NISQ Era, Quantum, 2023

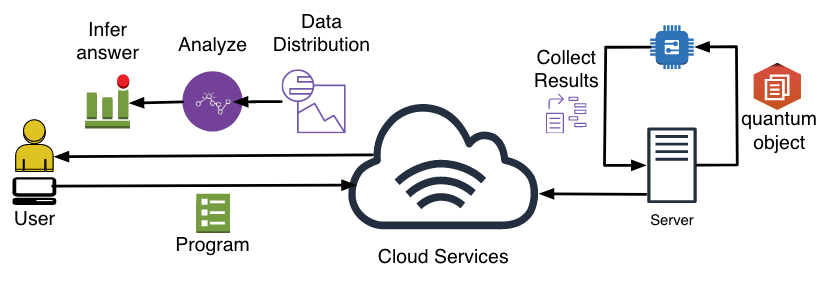

- NISQ quantum computers are prototypes and can be accessed through cloud service.

- Contention for quantum Computers: The rate at which quantum computers are being developed lags the rate of increase in the number of users.

- Resource Underutilization: Cloud quantum computers are severely underutilized.

- The wait times to access quantum computer hinders fast development and verification of quantum algorithms on real quantum computers.

---- Multi-programming NISQ

Overview of proposed framework

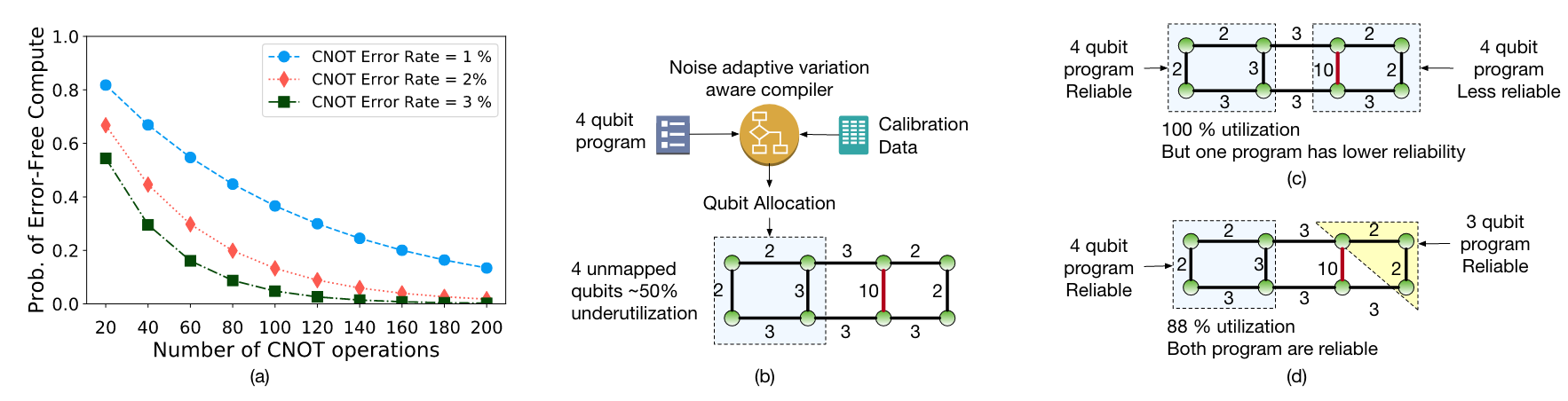

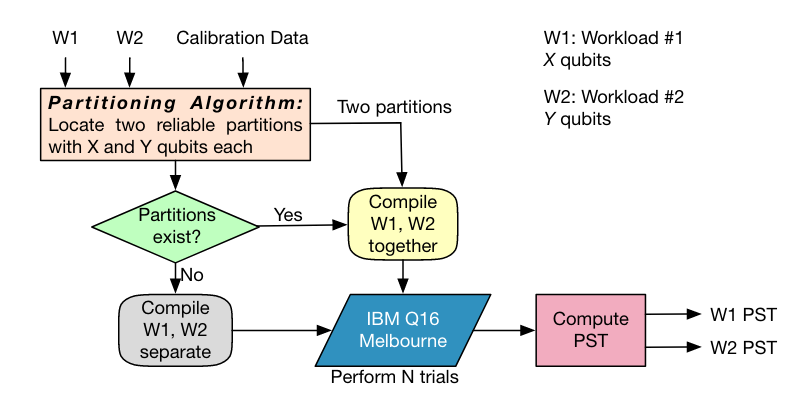

The ratio of the number of trials performed when both programs execute individually (baseline) to the total number of trials performed when the programs share resources. $$ TRF_{ij} = \frac{T_i^{independent} + T_j^{independent}}{T_{ij}^{shared}} $$

To evaluate application reliability we use the metric: Probability of a Successful Trial (PST), defined as the ratio of number of successful trials to the total number of trials performed $$ PST = \frac{\text{Number of successful trials}}{\text{Total number of trials}} $$

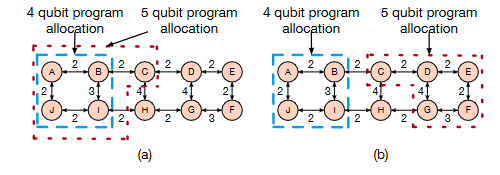

Restrictions on qubit Allocation

Restrictions on qubit Movement

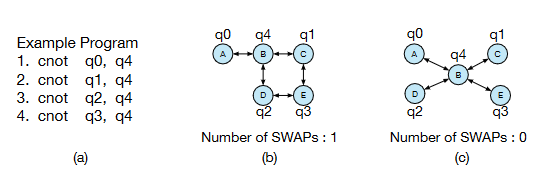

When a quantum computer is partitioned for multi-programming, application reliability can vary based upon the number of SWAPs inserted. This depends on the network topology of the assigned partition.

When a quantum computer is partitioned for multi-programming, application reliability can vary based upon the number of SWAPs inserted.

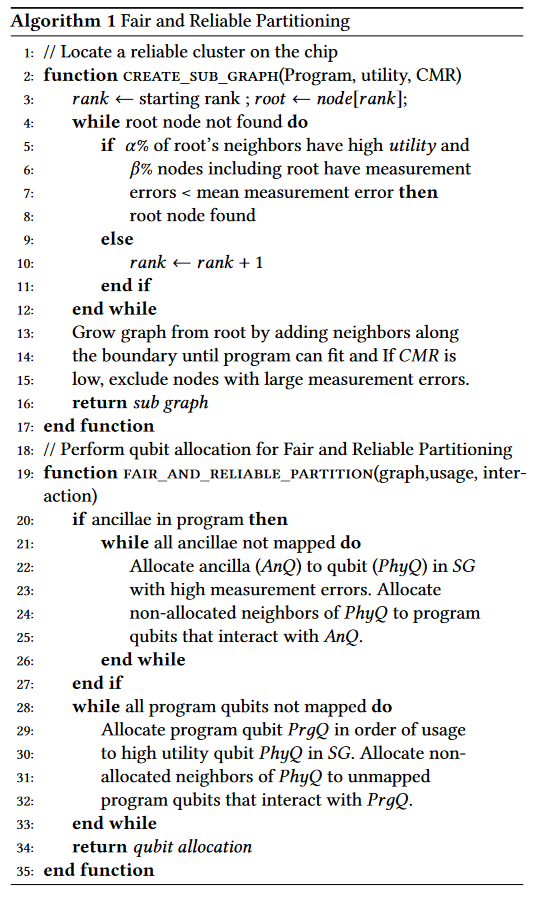

Key insights

There exists more than one reasonably good cluster of qubits on a quantum substrate with similar error rates.

Algorithm $$ Utility=\frac{\text{Number of links}}{\text{Sum of link errors}} $$

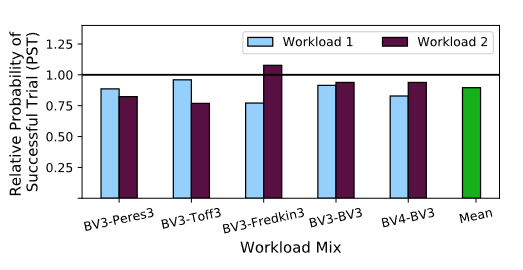

2$\times$ throughput with slight loss of program fidelity.

QuCloud: A New Qubit Mapping Mechanism for Multi-programming Quantum Computing in Cloud Environment

- Construct Hierachy Tree based on community detection.

- Partition and Allocation. Allocate more reliable region for circuit with dense CNOTs.

The CDAP algorithm is based on FN algorithm https://github.com/526536686/Fast-Newman-Algorithm

QuOS operating on compilation time?? Classical system operating on executables.

- Advances in compilation for quantum hardware -- A demonstration of magic state distillation and repeat-until-success protocols, Quantum, 2023, Microsoft

- Enabling Multi-threading in Heterogeneous Quantum-Classical Programming Models, IPDPSW, 2023

TL;DR

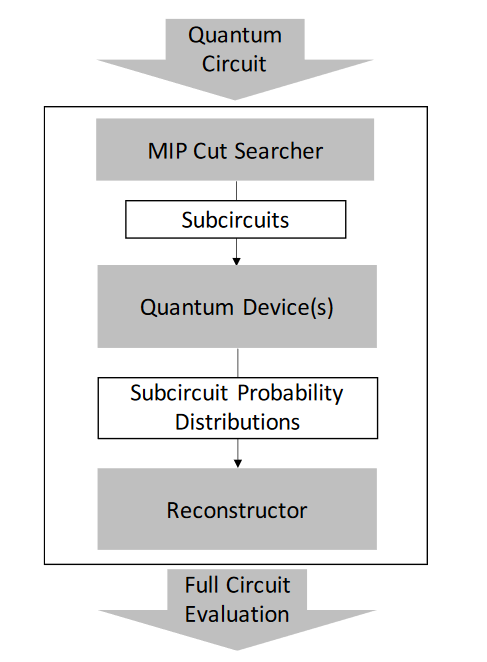

- Automatic scheme that uses mixedinteger programming to find optimal cuts for arbitrary quantum circuits.

-

Exponential Search Space. For general quantum circuits with 𝑛 quantum edges, this task faces an

$\mathcal{O}(n!)$ combinatorial search space. - Exponential Post Processing. Scale the classical postprocessing is challenging since large quantum circuits have exponentially increasing state space.

Quantum circuit

MIP Cut Searcher $$ y_{v,c} \equiv \begin{cases} 1 \text{ if vertex }v \text{ is in subcircuit }c \ 0 \text{ otherwise} \end{cases}, \forall v \in V, \forall c \in C $$

objective: minimize the number of floating-point multiplications involved in the reconstructor.

where

key constraint: forcing vertices with smaller indices to be in subcircuits with smaller indices.

Classical Postprocessing

- Full definition

- greedy-subcircuit-order

- early termination

- parallel processing:???

- Dynamic definition

- Quantum computer runtime is negligible in the comparisons.

- At most 5 subcircuits with 10 cuts.

- MIP runtime is ignored.

- Why not compare with naive CutQC, i.e., manual cut?

- Why not compare CutQC with TN simulation?

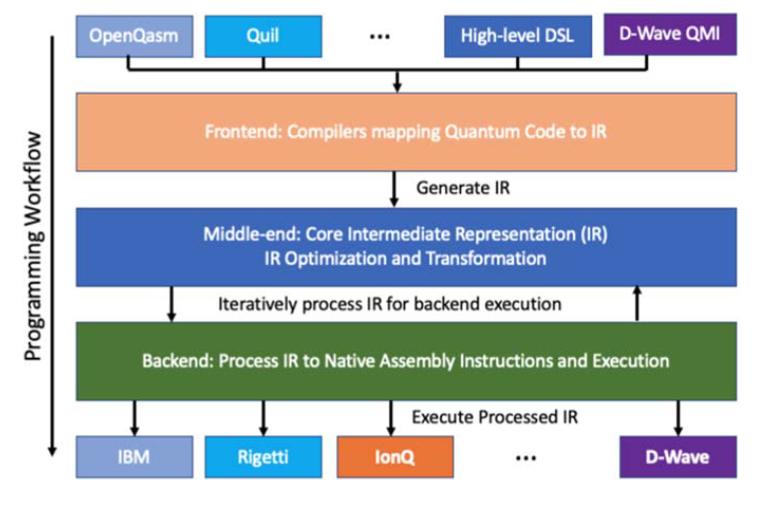

XACC: a system-level software infrastructure for heterogeneous quantum–classical computing, QST-2020, Oak Ridge National Laboratory

Motivation

- A quantum-accelerated computing model should adopt best practices and mirror the design of modern heterogeneous high-performance computing, which offers the advantage of improved performance through more refined control over execution scheduling and memory management.

- Along with tighter integration, the use of interpreted languages for controlling remote access execution must be replaced by lower-level, system software infrastructures, tools, and compilers for composing complex quantum–classical workflows.

Framework Architecture

Front End

Maps source strings expressing a quantum kernel to an IR instance.

- XACC provides an extensible quantum code transpilation or compilation interface that may be tailored to parse many different languages into a common IR for subsequent manipulation.

Middle Layer

Exposes an IR object model while maintaining an API for quantum programs that is agnostic to the underlying hardware.

- A critical middle layer concept is the IR transformation, which exposes a framework extension point for performing standard quantum compilation routines, including circuit synthesis, as well as the addition of error mitigation and correction techniques into the logical design.

Backend Layer

Exposes an abstract quantum computer interface that accepts instances of the IR and executes them on a targeted hardware device.

- The back-end layer provides further extension points mapping the IR to hardware-specific instruction sets and the low-level controls used to execute kernels.

Pros of Layered Approach

- Direct mapping of

$N$ languages into$M$ quantum devices would require$NM$ separate language-to-hardware mappings. XACC reduces the amount of work necessary to$N+M$ separate mapping implementations. The IR is the central construct connecting the front-end and back-end layers through a set of transformations.

- Unlike classical ML algorithms which are trained on millions of data points, training a QSVM requires us to process

$n^2$ circuits for$n$ data points, while testing takes$n \cdot m$ circuits.

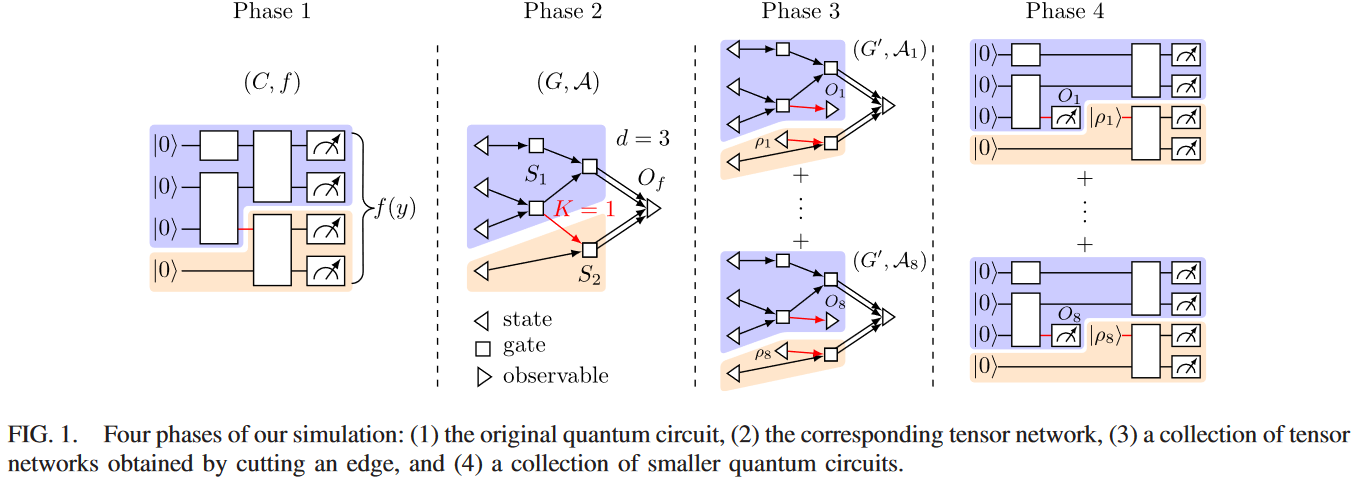

Partition a quantum circuit into multiple smaller fragments, each of which can be executed independently and parallelly on a smaller hardware.

Simulating Large Quantum Circuits on a Small Quantum Computer, PRL-2020

-

$(C,f)$ : a quantum-classical algorithm-

$C$ : An$m$ -gate quantum circuit -

$f:{0,1}^n\to [-1,1]$ :

-

-

$T(G,\mathcal{A})$ -

$G$ : A directed graph$G(E,V)$ -

$\mathcal{A}$ : A collection of tensors${A(v)}:v\in V$ .

-

Example

Can be cut into two fragments.

Can be cut into two fragments.

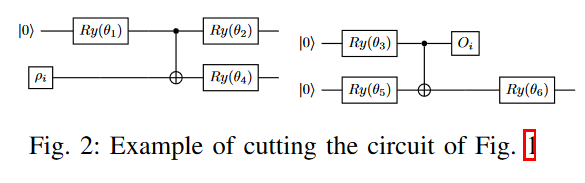

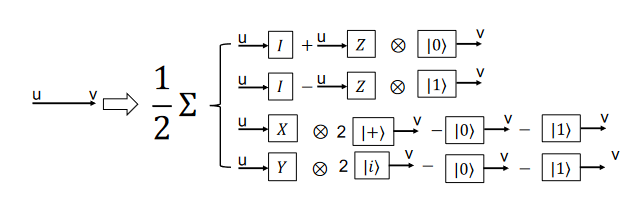

- Circuit cutting.

- Classical post processing.

Limitation

- Work for circuits with weak interaction strength.

- Post-processing time scales exponentially with the number of cuts.

CutQC

This figure illustrated what exactly happens when you cut a wire.

The input qubit

This figure illustrated what exactly happens when you cut a wire.

The input qubit

Split the circuit batch representing the data points of training and test sets such that they could be executed independently on multiple quantum hardware.

Quantum Cognitive Modeling: New Applications and Systems Research Directions

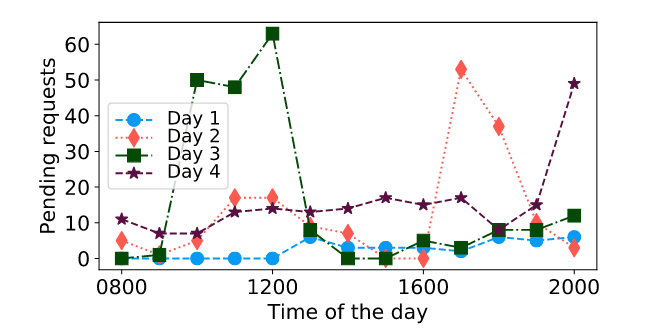

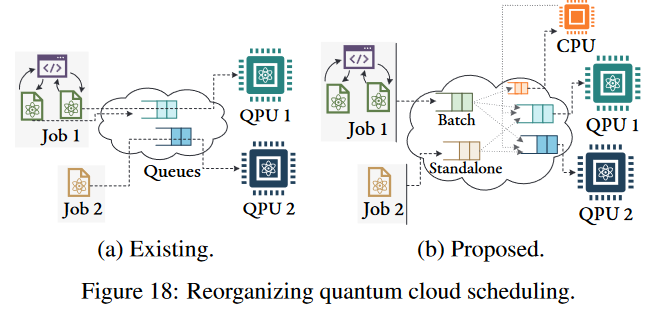

- Evaluate the potential impact of parallelism-aware cloud scheduling using data from real quantum systems.

Insights

- Users schedule each job directly into devicespecific queues, which cannot be migrated to other queues.

Proposal

- Split queues into an application-specific frontend, and a device-specific backend.

- Users submit jobs to the front-end that separately handles standalone, and batched jobs (iterative or parallel).

- These jobs are later scheduled into device-specific queues based on availability or user-preference.

- Scheduling entire jobs including its classical computation.

- Adding cloudlets [106] with classical compute (CPUs/GPUs) to support the Map-Reduce style parallelism.

Key Component

- Quantum Kernels: Executable quantum code instances that are compiled down the the quantum intermediate representation. These kernels are executed on quantum coprocessors or emulated quantum processors.

- Quantum Registers: CUDA Quantum provides a quantum memory model that enables one to think about general qudits of information, dynamic and static registers of those qudits, and whether those registers are owning or non-owning. CUDA Quantum defines a non-copyable unit of quantum information, the

cudaq::qudit<Levels>template type. Because it is non-copyable, instances of this type cannot be passed by value and must always be passed by reference, in an effort to avoid copying, or cloning, the underlying quantum information. - Generic Library Functions: A core aim of the CUDA Quantum platform is to create a robust collection of generic, fundamental primitives that can be used in a wide range of algorithms. These functions can be found in the

cudaq::namespace. These primitives can be applied to a wide variety of quantum codes. - Interoperability: Seamless integration with existing classical parallel programming models, such as CUDA, OpenMP, and OpenACC. This interoperability allows for the development of hybrid quantum-classical applications that can fully exploit the computational capabilities of both classical and quantum hardware.

Case Study -- VQE

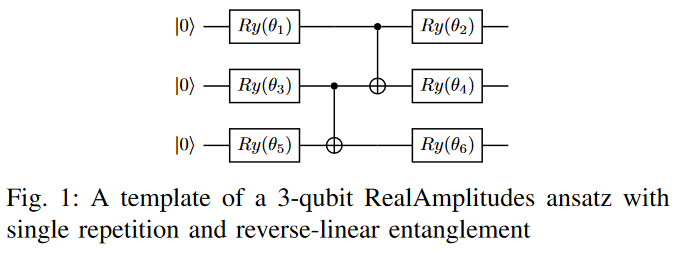

- Parameterized Ansatz: A CUDA Quantum kernel expression that takes a vector of parameters as input. The molecular Hamiltonian is transformed to the spin Hamiltonian via Jordan-Wigner or other transformation.

- Hamiltonian Operator: A quantum mechanical operator, represented as the built-in

spin_optype in CUDA Quantum. This operator can be constructed using the Paulix(int),y(int), andz(int)function calls - Classical Optimizer: A user-specified classical optimization algorithm for searching the minimum expectation value. In CUDA Quantum, the classical optimizer is a general concept within the language specification that can be subclassed to implement specific optimization strategies, either gradientbased or gradient-free.

- VQE Workflow: A standard library function provided by CUDA Quantum for executing the entire VQE algorithm. This function takes the quantum kernel instance modeling the state preparation ansatz, the Hamiltonian operator, the classical optimizer, and the total number of variational parameters as input. It returns a structured binding that contains the optimal eigenvalue and the corresponding optimal parameters for the state preparation circuit.

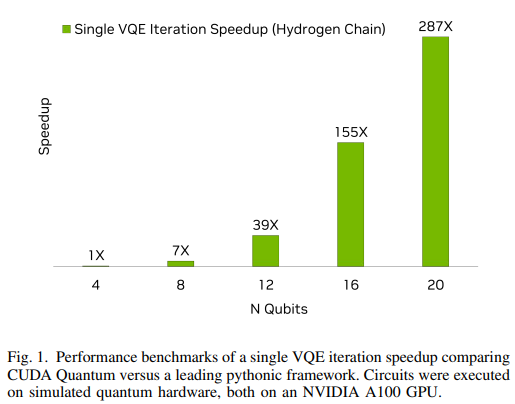

Performance

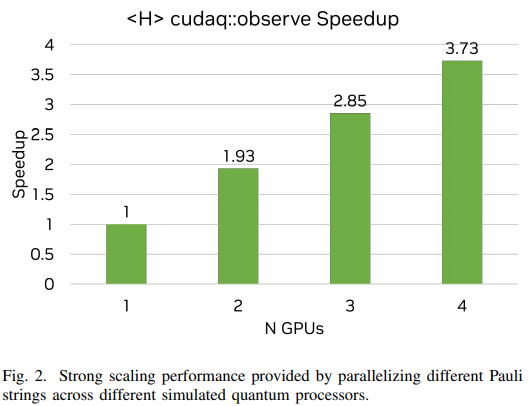

One More Thing CUDA Quantum also enables users to explore quantum computing configurations that are not available today but have potential to speedup quantum workloads in the future. For VQE, a key component of the workflow is to obtain measurements of the energy of the ansatz. This is achieved by measuring the expectation value of Pauli strings for a given execution of a parameterized circuit. Since many different Pauli strings must be measured for a given parameterized circuit, this workload can be embarrassingly parallelized over multiple quantum processors or emulated quantum processors.

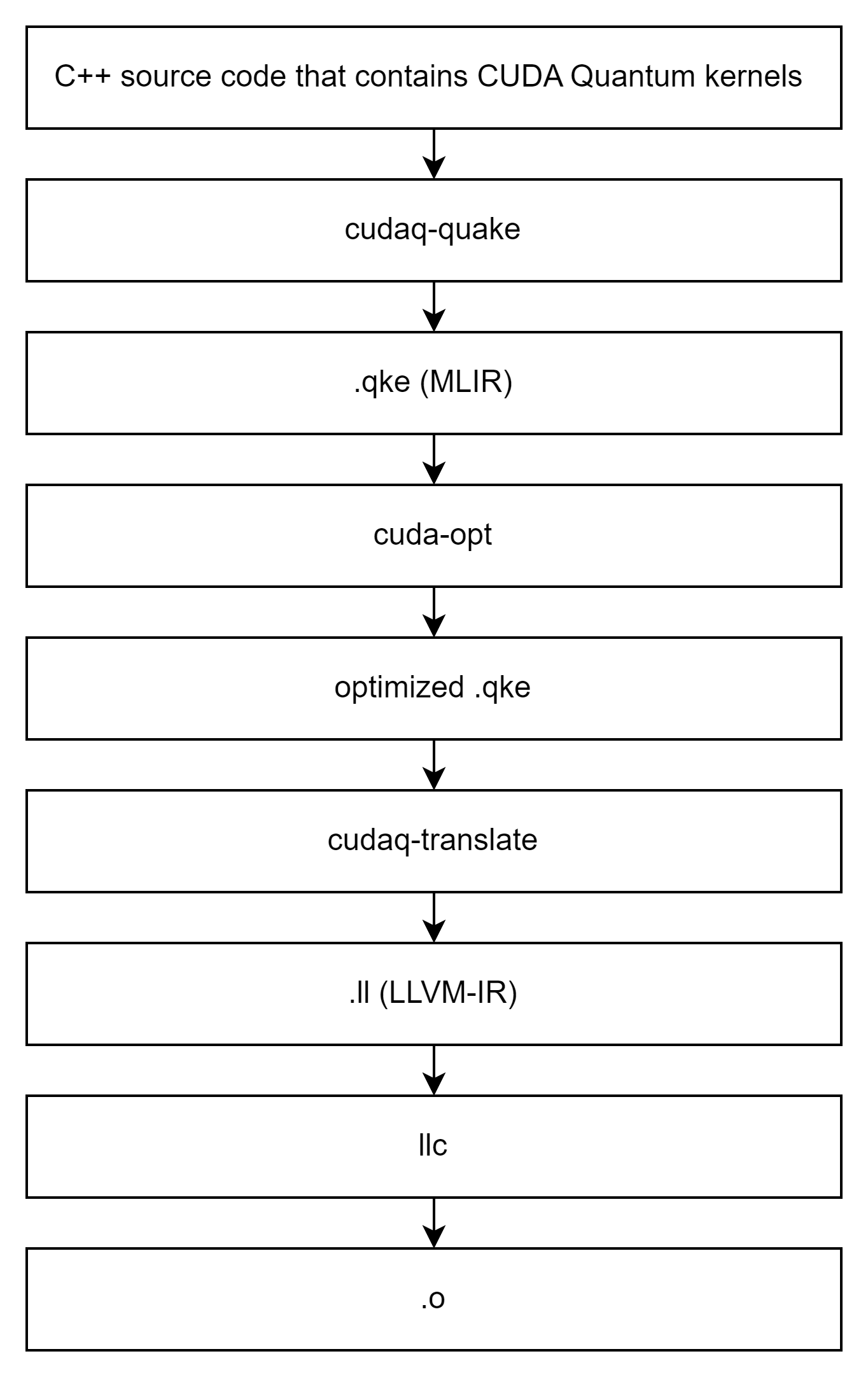

cudaq-quake

Convert the quantum kernel in a c++ source file to an MLIR file.

MLIR (Multi-Level IR) is a compiler infrastructure that uses a uniform intermediate representation to represent code at multiple levels of abstraction. It is used by CUDA Quantum to represent quantum programs.

Here is an example of compiling a simple C++ source file containing CUDA Quantum code into an MLIR file:

// example.cpp

#include <cudaq.h>

__global__ void bell_state(Complex* q) {

H(q[0]);

CNOT(q[0], q[1]);

}

int main() {

bell_state<<<1,2>>>(nullptr);

}We can compile this to MLIR using cudaq-quake:

$ cudaq-quake example.cpp -o example.mlir

This will emit MLIR for the quantum kernel bell_state to example.mlir.

The MLIR will look something like:

module {

func @bell_state(%q: !cudaq.complex<f64>*) {

%0 = cudaq.getelementptr %q[%c0_i32] : (!cudaq.complex<f64>*, i32) -> !cudaq.complex<f64>*

cudaq.H %0 : !cudaq.complex<f64>*

%1 = cudaq.getelementptr %q[%c1_i32] : (!cudaq.complex<f64>*, i32) -> !cudaq.complex<f64>*

cudaq.CNOT %0, %1 : !cudaq.complex<f64>*, !cudaq.complex<f64>*

return

}

} The key points are:

- MLIR represents quantum operations like H, CNOT as function calls

- Metadata like complex types and pointers are explicitly declared

- Higher-level structure of the program is maintained

This MLIR can then be optimized and lowered to different backends like QIR.

So in summary, cudaq-quake can be used to compile CUDA Quantum C++ into MLIR to bring it into the MLIR pipeline. The MLIR contains all the necessary information while staying target-independent.

Key Ideas

- Use

std::threadandstd::asyncto enable multi-threading- Implement thread-safety using mutex

- Support thread-qpu mapping by adding a QPU manager

Limitation

- Assume classical operating system to manage quantum threads?

- Efficient Long-Range Entanglement using Dynamic Circuits, IBM

- Universal Qudit Gate Synthesis for Transmons, IBM

- Electron charge qubit with 0.1 millisecond coherence time, Nature Physics