A Systems-Level Deep Dive for C and C++ Developers

Disclaimer: ChatGPT generated document.

Below is a full, deep, and comprehensive article on endianness, alignment, and padding, written from a systems / C++ perspective and aimed at someone who already thinks about ABI, performance, and portability.

I’ll build this bottom-up, starting from physical memory, then CPU rules, then language rules, and finally real-world consequences in C++.

Before anything else, lock in this model:

Memory is a linear array of bytes.

Everything else—int, float, structs, arrays, objects—is an interpretation layered on top of that byte array by:

- The CPU

- The ABI

- The compiler

- The language rules

Most bugs around endianness, alignment, and padding happen when we forget who is responsible for which rule.

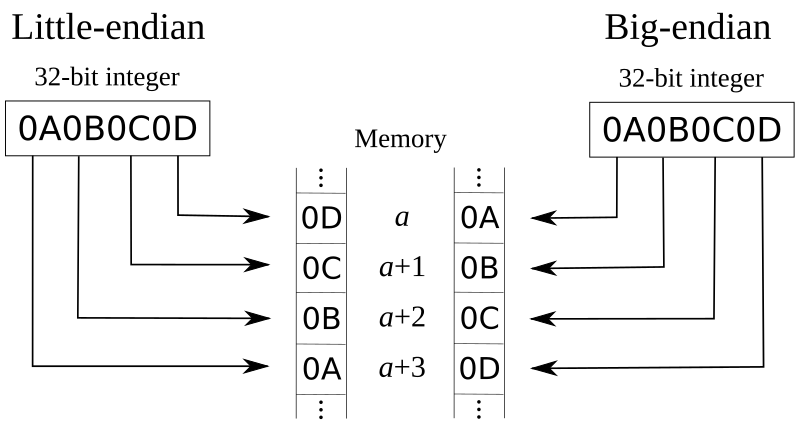

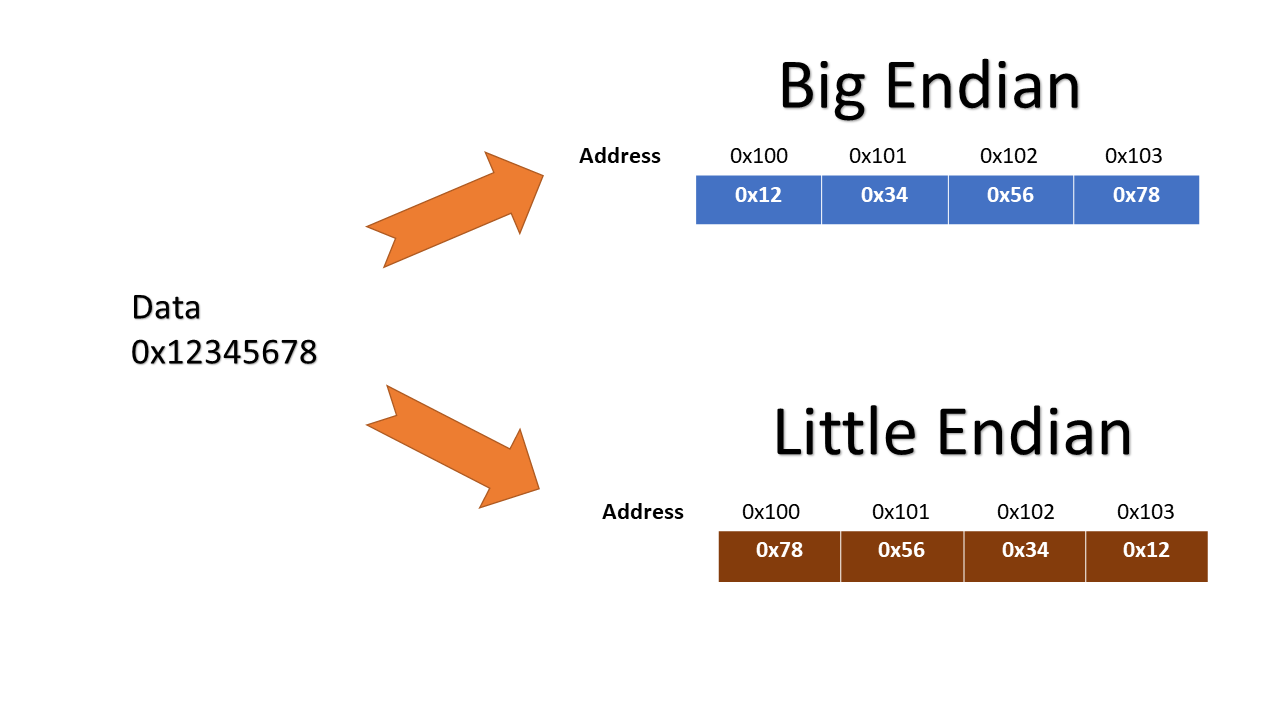

Endianness defines how multi-byte scalar values are laid out in memory.

Consider a 32-bit value:

0x12 34 56 78

This is a number. Memory needs to store it as bytes.

| Endianness | Lowest address | Highest address |

|---|---|---|

| Little | 78 56 34 12 |

→ |

| Big | 12 34 56 78 |

→ |

- Little-endian: least significant byte first

- Big-endian: most significant byte first

Modern CPUs (x86, ARM in LE mode, RISC-V) are little-endian because:

- Incremental arithmetic is simpler

- Casting smaller types is cheaper

- Historical inertia (x86 dominance)

Big-endian still exists in:

- Networking protocols (network byte order)

- Some DSPs

- Legacy systems

Endianness affects only:

- Multi-byte scalar objects (

uint16_t,uint32_t,float,double, pointers)

It does not affect:

- Byte-sized objects (

char,std::byte,uint8_t) - Bitwise operations inside a register

- Object identity

In C++:

- Endianness is implementation-defined

- You must not assume little-endian unless you explicitly restrict platforms

C++20 finally gives you a way to ask:

#include <bit>

if constexpr (std::endian::native == std::endian::little) {

// ...

}Important distinction:

Endianness rearranges bytes, not bits.

For example, IEEE-754 floats:

- Have a defined bit layout

- But the byte order of those bits depends on endianness

That’s why:

memcpypreserves bit patterns- Serialization must normalize byte order

Networking standardized on big-endian so all machines agree.

Hence:

htonl() // host → network

ntohl() // network → hostIf you send raw structs over the wire without conversion:

- ❌ Breaks on different endianness

- ❌ Breaks on different padding

- ❌ Breaks on different alignment

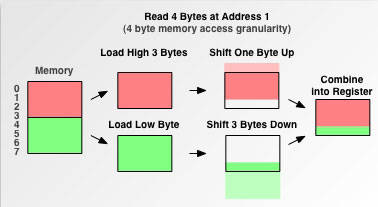

Alignment is a constraint imposed by the CPU:

Certain types must be stored at memory addresses divisible by some power of two.

Example:

uint32_t→ alignment 4- Must live at addresses

0x...0,0x...4,0x...8, …

Alignment exists because:

- CPUs fetch memory in chunks (cache lines)

- Misaligned loads may:

- Take multiple cycles

- Require multiple memory accesses

- Trap entirely on some architectures

| Architecture | Misaligned access |

|---|---|

| x86 | Allowed, slower |

| ARM | Sometimes traps |

| SPARC | Traps |

| RISC-V | Often traps |

So alignment is not “optional paranoia” — it’s hardware law.

C++ exposes alignment via:

alignof(T)Examples:

alignof(char) == 1

alignof(int) == 4

alignof(double) == 8

alignof(void*) == 8 (on 64-bit)The compiler must:

- Place objects at aligned addresses

- Insert padding when necessary

- Reject misaligned references

C++11 introduced over-aligned types:

struct alignas(64) CacheLine {

int data;

};Used for:

- Cache-line isolation

- False-sharing prevention

- SIMD data

Classic bug:

char buffer[16];

int* p = reinterpret_cast<int*>(buffer + 1); // ❌ UBEven if it “works on x86”:

- UB by the language

- May crash on ARM

- Sanitizers will flag it

Padding is unused space inserted by the compiler to satisfy alignment rules.

It exists:

- Between struct members

- At the end of structs

Given:

struct S {

char c;

int i;

};Memory layout (typical):

offset 0: char c

offset 1–3: padding

offset 4–7: int i

Why?

intrequires alignment 4- Compiler inserts padding to satisfy it

struct T {

int i;

char c;

};Layout:

int (4 bytes)

char (1 byte)

padding (3 bytes)

Why?

- Arrays of

Trequire each element aligned properly

Padding:

- Contributes to

sizeof(T) - Is copied by

memcpy - Is compared by

memcmp

But:

- Padding bytes have indeterminate values

- Reading them is undefined behavior

This breaks:

- Hashing

- Serialization

- Equality comparisons

#pragma pack(push, 1)

struct Packed {

char c;

int i;

};

#pragma pack(pop)Result:

- No padding

- Misaligned

int - Possible traps or slow accesses

Use only for:

- Wire formats

- Disk layouts

- Explicit byte manipulation

Never use packed structs for:

- Normal computation

- Hot paths

- Arbitrary pointer casting

A struct layout depends on:

- Endianness

- Alignment rules

- Padding rules

- ABI

- Compiler

This means:

You cannot safely serialize a struct by dumping its bytes.

Ever.

If you send this over the network:

struct Packet {

uint32_t id;

uint16_t len;

char flag;

};You have three independent problems:

- Endianness of integers

- Padding between members

- Alignment expectations on the receiver

Only serialize explicitly defined byte sequences.

Example:

uint32_t id = htonl(packet.id);

uint16_t len = htons(packet.len);Or use:

- Protocol Buffers

- FlatBuffers

- Cap’n Proto

- Manual byte packing

- Assume nothing

- Normalize when crossing boundaries

- Use

std::endian - Use

std::bit_cast, not unions

- Respect

alignof - Never cast misaligned pointers

- Use

alignasfor performance, not correctness - Be wary of packed structs

- Never rely on struct layout

- Never

memcmpstructs - Never serialize raw structs

- Initialize everything if hashing

- Endianness: “Byte order matters when bytes leave the CPU.”

- Alignment: “The CPU decides where objects may live.”

- Padding: “The compiler inserts space you didn’t ask for.”

Given your background in:

- Modern C++

- Networking

- Low-level abstractions

- Cross-platform libraries

These rules directly affect:

- Socket APIs

- Binary protocols

- Zero-copy buffers

- SIMD and cache-line tuning

- ABI stability

If you want, next we can:

- Analyze real compiler-generated layouts

- Deep-dive ABI guarantees vs myths

- Design a portable binary format from scratch

- Audit a real struct for hidden UB

Just tell me how far you want to go.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endianness

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Data_structure_alignment

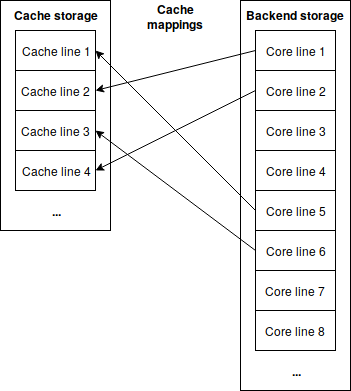

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CPU_cache

https://commandcenter.blogspot.com/2012/04/byte-order-fallacy.html