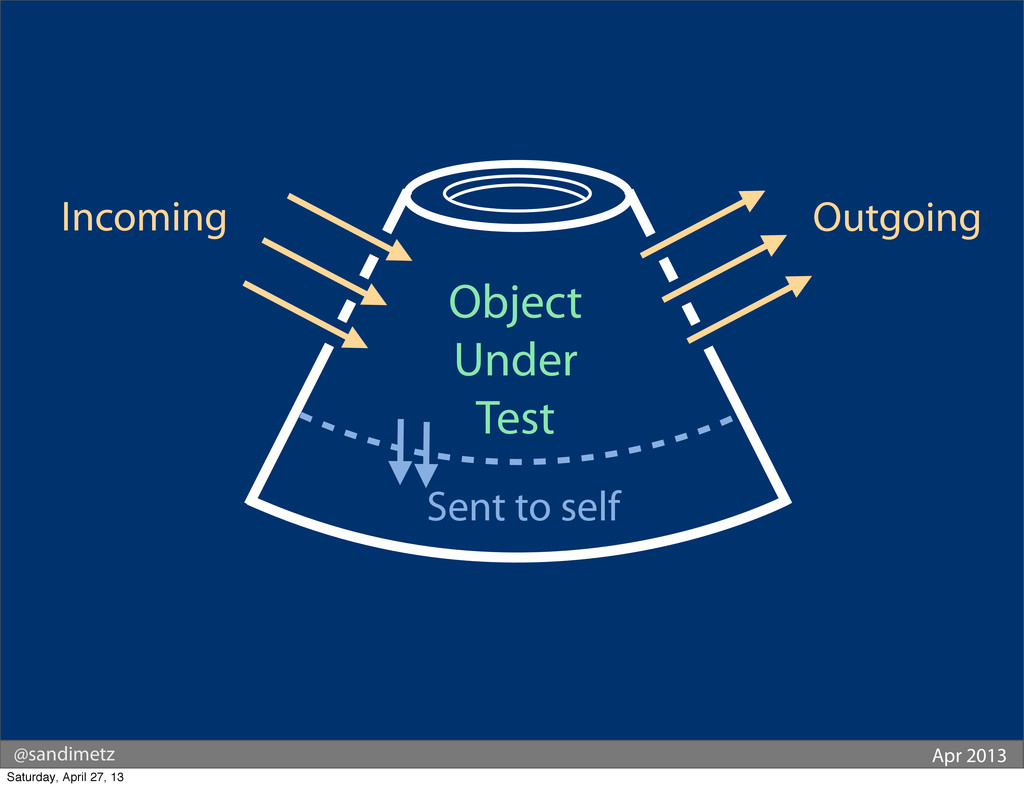

Look at the following image...

...it shows an object being tested.

You can't see inside the object. All you can do is send it messages. This is an important point to make because we should be "testing the interface, and NOT the implementation" - doing so will allow us to change the implementation without causing our tests to break.

Messages can go 'into' an object and can be sent 'out' from an object (as you can see from the image above, there are messages going in as well as messages going out). That's fine, that's how objects communicate.

Now there are two types of messages: 'query' and 'command'...

Queries are messages that "return something" and "change nothing".

In programming terms they are "getters" and not "setters".

Commands are messages that "return nothing" and "change something".

In programming terms they are "setters" and not "getters".

- Test incoming query messages by making assertions about what they send back

- Test incoming command messages by making assertions about direct public side effects

- Messages that are sent from within the object itself (e.g. private methods).

- Outgoing query messages (as they have no public side effects)

- Outgoing command messages (use mocks and set expectations on behaviour to ensure rest of your code pass without error)

- Incoming messages that have no dependants (just remove those tests)

Note: there is no point in testing outgoing messages because they should be tested as incoming messages on another object

Command messages should be mocked, while query messages should be stubbed

Contract tests exist to ensure a specific 'role' (or 'interface' by another - stricter - name) actually presents an API that we expect.

These types of tests can be useful to ensure third party APIs do (or don't) cause our code to break when we update the version of the software.

Note: if the libraries we use follow Semantic Versioning then this should only happen when we do a major version upgrade. But it's still good to have contract/role/interface tests in place to catch any problems.

The following is a modified example (written in Ruby) borrowed from the book "Practical Object-Oriented Design in Ruby":

# Following test asserts that SomeObject (@some_object)

# implements the method `some_x_interface_method`

module SomeObjectInterfaceTest

def test_object_implements_the_x_interface

assert_respond_to(@some_object, :some_x_interface_method)

end

end

# Following test proves that Foobar implements the SomeObject role correctly

# i.e. Foobar implements the SomeObject interface

class FoobarTest < MiniTest::Unit::TestCase

include SomeObjectInterfaceTest

def setup

@foobar = @some_object = Foobar.new

end

# ...other tests...

end

@Integralist,

How is this different from black-box testing and glass-box testing?

The description of testing philosophy above seems to be similar to black-box testing, but you typically need a combination of black-box testing and glass-box testing because black-box testing doesnt catch all the potential flaws in the program. Without knowing how the function is implemented, you maynot create test-cases which will catch the corner cases.